Gender equality study explores barriers women in Persian Gulf still face in oilfield careers

Industry has shown progress, but more leadership will be needed to help women enter field-based roles, upper management

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

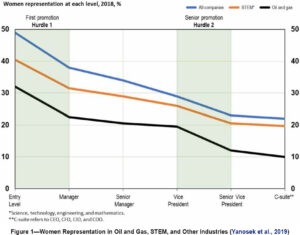

As drilling activity continues to ramp up across the Middle East, the growing need for a competent workforce also becomes more evident. To fill this talent gap, many countries in the region have provided more opportunities in recent years for its female workforce, allowing women to take advantage of higher education and industry-specific training.

Still, a gender imbalance in the workforce remains. Texas A&M University at Qatar (TAMUQ) and Northwestern University in Qatar cited that as the key motivation behind a recent study exploring the obstacles that female petroleum engineers face.

To gauge the oil and industry’s progress on gender equality in the workforce – both in Qatar and in the wider Persian Gulf region – the two schools conducted interviews in 2020-2021 with nine women and three men working in the industry. Based on the personal experiences shared by those interviewees, the schools analyzed the findings and then provided recommendations for organizations to help support women across all career levels. In particular, the study called for more opportunities and encouragement for women to pursue upper management positions.

“We’re trying to see what the challenges are,” Albertus Retnanto, Professor of Petroleum Engineering at TAMUQ, said of the project’s goals. “What’s happening to women when they’re looking to get in the industry, and what happens to them once they get here? What’s the progress? Some women have built careers here and are starting to move up the ranks, but there is a leak in the pipeline, and it’s important for us to see why,” he said in a presentation at the 2022 SPE ATCE in October.

Challenges in hiring and in the workplace

The 12 participants who were interviewed included field engineers and managers working within the oil and gas industry in areas like reservoir performance and digital integration; some were also academics in the petroleum engineering field. Although not every participant was working in Qatar at the time of the study, they each had ties to the country, either through education or former employment. Companies with employees represented in the study include BP, ConocoPhillips, Halliburton, QatarEnergy, Shell and SLB.

Among the top challenges the participants cited when talking to the researchers were a lack of policies or initiatives to promote women into executive positions, as well as explicit discouragement or even discrimination by coworkers and managers during the recruiting and hiring process. For instance, female participants said they had to deal with biased assumptions and overly personal interview questions that were irrelevant to their professional capabilities and experiences.

Several participants in the study also said they saw a stigma placed on women who wanted to take on technical field-based jobs. One woman noted that she was frequently questioned on why she would want to study petroleum engineering and work in the oilfield, and was even told that women were better suited for office-based positions. Another woman noted that a recruiter suggested she not apply for a specific position because it was a “very male job.”

Both men and women interviewed in the study pointed out that female new-hires were often sidelined into non-technical positions with limited opportunities to advance or have influence. This created a negative environment where other women would then seek office-based jobs instead of field jobs in order to avoid being scrutinized by male coworkers.

Participants also discussed the cultural and social barriers that women had to confront. This included a lack of proper accommodations for women working on offshore rigs – several female interviewees mentioned, for example, a lack of women-only restrooms. There is often also a lack of PPE fitted for women, including coveralls and headgear for women who wear a hijab.

The study also noted that company restrictions on women traveling alone was still common; one participant said her employer does not allow its female employees to travel without a mahram, or a male blood relative. Policies like this can restrict women from pursuing and exploring the various opportunities that their employer offers, like traveling to industry conferences or business meetings, or transfers to foreign countries.

One male participant who was interviewed suggested that appointing more women to managerial positions can help to address some of these issues. The study noted his comment around how cultivating “a diversity of gender allows us to be a lot more effective and solve problems in a smart way versus having only one way of thinking.”

One female participant said she has seen, in many instances, that men are willing to help women when they face a lack of accommodations – for instance, not objecting when women have to use men’s restrooms on a rig. At the same time, she expressed skepticism that the industry will see significant change – especially in terms of providing women-specific accommodations – until there are more female managers setting policy and more women working at wellsites.

Successes and suggestions

While the experiences shared by the participants clearly show there is a need for improvement, the study also pointed to signs of progress. BP’s Young Adventurers camp in the United Arab Emirates is a good example. While it’s not meant only for women, it is inclusive of women and encourages them to consider engineering careers. The camp puts participants through physical challenges, such as raft building, abseiling and other team activities that encourage campers to use engineering skills and knowledge. The campers are divided by gender, and the women’s camp features an all-female staff.

One woman in the study said she participated in the camp when she was younger, and even cited the experience as a key factor in her decision to study engineering in school and, ultimately, begin an oilfield career. She now works as a petroleum engineer for BP and has continued her involvement with the camp as a volunteer.

The study cited this statement from her: “There are still these places within this region that a girl can’t even imagine that she can be an engineer or there could be female engineers. That’s why I want to continue this program, to make sure these girls know that there are engineers in the field, and if she is interested and wants to do it, then she can.”

Another example of progress is what universities in the region are doing to prepare female students for jobs in the oilfield, Dr Retnanto said. At TAMUQ, for example, women made up nearly 70% of its petroleum engineering graduating class in 2021. Every year, the school organizes field trips for all of its petroleum engineering students, including women, to visit onshore E&P sites.

Overall, all the participants in the study said promoting gender inclusivity within the industry will require even more effort from company leadership. They suggested that companies leverage internship programs to incentivize more female students to consider careers in oil and gas, as well as programs that encourage women to enter managerial roles once they start their careers. One male participant in the study encouraged women to enhance their technical capabilities by participating in as many hands-on training and internships as they can.

Flexible work hours could also go a long way toward promoting gender inclusivity. Several women said they believe schedule flexibility and remote work can allow organizations to retain more female employees who may face challenges around childcare and caring for aging relatives. One male participant said his employer has given more attention to this in recent years by providing female employees with a blueprint for how to return to work after they take maternity leave.

Other things that women themselves could do to promote gender equality include taking the initiative to ask questions, or speaking up when they see unfair treatment. The participants also encouraged women to report discriminatory remarks they encounter in the workplace to their managers, and said it was important for women in the workplace to support one another. DC

More information available in SPE 210236, “First-Hand Perspectives of the Pro-Female Notion in the Oil and Gas Industry in the Gulf.”