Preemptive under-investment in oil/gas likely to lead to recurrent economic crises in coming years

IHS Markit’s Daniel Yergin: Despite rhetoric around energy transition, reality is that world will need affordable energy, so demand for oil and gas will grow into 2030s

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

Daniel Yergin is Vice Chairman of IHS Markit.

How optimistic are you about the trajectory of the oil price in the coming months? Is it something that you feel the industry should be concerned about right now?

Our view is that oil will stay in the $65-90 range. There’s a floor there that OPEC+ provides, and there’s a ceiling, as well. Could it go above or below that? Obviously, geopolitical events or disruptions could push the price higher, but $65-90 is reasonable as a planning assumption.

Within that range, our expectation is that prices will average in the mid-$70s this year, although we have to be very cognizant that events – be they political, economic or COVID-19 related – could change the outlook, and swiftly.

What kind of geopolitical events would have the greatest impact on the oil market?

Any forecast is contingent on events because you don’t know what’s going to happen to world GDP or what Vladimir Putin’s going to do. Ukraine is a flashpoint. Clearly, the uncertainty about Iran and its nuclear program is a backdrop to the global oil and gas industry. There’s not a big focus on it right now, but Iran is a lot more advanced in its nuclear program today than it was when it negotiated the original nuclear deal in 2015. Then there’s the tension around East Asia. I spent some time in my latest book (“The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations”), writing about the South China Sea as the cauldron for tension between the United States and China. That’s the one place where, literally, the US and Chinese Navy have come very close to collision, so that area, along with Taiwan, is among the big risks in 2022 for the energy market – and indeed the world economy.

The book deals a lot with the energy transition. In fact, you call it the defining global issue right now. You wrote about the world moving to a “challenging post-Glasgow” phase, referring to last year’s COP26 conference. What makes this phase challenging, and what will those challenges mean for oil and gas production?

There is a lot of coalescing around the net-zero carbon target by 2050, but there’s no agreement at all, or even a realistic outline, of how to get there and what is the role of the oil and gas industry. Even in IHS Markit’s very aggressive energy transition scenario – what we call a “Green Rules” scenario – we still see a significant role for oil and gas in 2050, but there are a lot of political leaders who just won’t acknowledge that. I think that struggle is what this post-Glasgow era is about.

This era is also about looking at economic costs. It was very striking that, at the same time that COP26 was happening in November, Europe and Asia were both gripped by a severe energy crisis. There is a concern, particularly as people try and push the 2050 goals into 2030, that what happened – which is still reflected in commodity prices there – will reoccur. We may see recurrent economic crises from trying to push so hard.

There’s also a major disconnect between the targets that have been put out there and the supply chains for achieving them in terms of requirements for the minerals that are critical in producing electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels. It takes a long time to bring a major offshore oil or gas field on stream, but it takes even longer to bring a new mine into operation – about 16 years on average. It’s a disconnect between the objectives and the supply chains to support those objectives.

You can’t go anywhere in the world now where people don’t talk about the energy transition. Trying to transform the energy foundations of what is about a $90 trillion world economy in a 30-year time frame is breathtaking, to say the least. It’s breathtaking in its ambition. You can have all the discussions you want, but the scale and complexity of this endeavor is just not recognized, as well as the degree to which this impacts the world economy.

The US shale industry was hit particularly hard by the 2020 oil price downturn, but it seems to have stabilized. What have been the key factors in the recovery, and do you see the recovery continuing this year?

The US oil and gas industry is very resilient. Just two years ago, people were writing obituaries for the shale industry. That always seemed wrong to me. Recovery was always a question of oil price. What we’ve seen in terms of recovery is the shale industry’s flexibility and innovative capacity: You have lots of companies and lots of different people with different ways of attacking challenges.

Consolidation has also been important. Because of these things, the industry is back on a growth track – not a growth track where we see production increasing by 2 million bbl/day as in the last decade, but a track where we can say the US is back as one of the key determinants of the global oil market. For the last year to 18 months, oil production has really been dominated by OPEC+, but the US is definitely back.

One thing we’ve seen in the past couple of years, particularly among US shale operators, is the prioritization of shareholder returns over growth. Is this something that we’re going to continue to see moving forward?

Yes. We’re really in what I refer to in “The New Map” as “the second shale revolution.” The first revolution was the amazing emergence of shale itself – on a scale and at a speed the world had never before seen in terms of the emergence of new supply. The second is a new social contract between companies and the investment community, and one which involves real returns to investors.

What we have seen within the shale industry is a shift from pursuing growth at any cost to asking “at what cost?” That mantra of capital discipline is now embedded in the DNA of the industry. The industry recognizes that it has to be responsive to shareholders, particularly at a time when ESG has become much more important. You’ve got to return value to your shareholders so you can show them why they should hold your shares. That’s been a big evolution in thinking, and you’re seeing it in the interaction of these companies with the investment community.

We’re at this interesting point now where it’s possible find a balance between returning money to shareholders and investing. More companies are starting to think more in growth terms again, but in a more disciplined way.

The relationship between the oil and gas industry and the investment community is certainly of great interest, particularly as investors continue to place a higher priority on ESG. Should this be a concern for the industry?

The ESG pressures are inescapable, not just from an investment standpoint but also from a regulatory standpoint. The regulatory pressures are happening in Europe, and we’re going to see it coming to the United States where the SEC, and even the Federal Reserve, are becoming climate regulators, on top of everything else they do.

Companies are adjusting to these new pressures, although in different ways. Reducing the carbon footprint of your operations is one. And more people are talking about carbon advantaged barrels, being competitive in terms of not just price and quality but also the carbon footprint of production in a barrel. Those are all becoming part of the workflow of the industry.

Do you think we’re going to see an increase in global crude supply in 2022? If so, where do you see that increase coming from?

We know some of the OPEC+ countries cannot produce at their own target quotas right now, but we do see the most important growth coming from the United States. For the United States, it may be as much 700,000 to 900,000 bbl/day growth over 2022. There will also be growth from Brazil, among other countries.

Since you mention Brazil, that country has had some mixed results from its pre-salt auctions over the last couple of years. What do you think those results say about the overall challenges of countries trying to attract E&P investment?

When it comes to drawing investment, the message I try to give to governments around the world is: The name of the game is different. This is no longer a question of adding reserves or adding barrels. It’s about being cost efficient. Governments need to have a different mindset if they want investment, because they’re competing with other countries. That’s a message that governments are often late to get, or they don’t want to hear it. It’s a competitive industry, and companies are going to be more selective.

Capital is mobile. The decline in capital investment is quite striking for the upstream sector, and that’s sending a message about tight supply down the road. If you want to be in the game for the future and if you want investment, you have to be competitive in terms of the fiscal system, the regulatory environment, and in terms of the quality and timeliness of decision making. The warning light is there for countries – lackluster responses to bidding rounds.

You said you expect oil demand to continue increasing into the 2030s even as IOCs are under pressure to invest more in renewable energy production. Do you think that pressure will have an impact on oil and gas supply, and if so, what issues do you think the disconnect between reduced supply and increased demand will create for the industry?

Yes, there’s a lot of pressure on the IOCs, and there’s also a wide disparity in the strategies that they’re adopting. They’re all being pressed to either announce net-zero carbon goals or adopt low-carbon strategies, and to be more careful and cautious in their investments. That’s where we see the cuts in upstream budgets.

What does it mean? When you look down the road, you see that oil demand will continue to grow until around the early 2030s. That supply has to come from somewhere. This could lead to recurrent tight markets.

There are two things that come from this. First, tight markets favor national oil companies that are continuing to grow their capacity, such as Saudi Aramco and ADNOC. Second, we have to go back to the risk of recurrent crises. I’m preoccupied with the risk of what I call preemptive under-investment, where we see pressure from governments, regulators and investors not to invest in new supply. The result of this under-investment is recurrent tight markets and volatility in price – and government interventions.

What happened last autumn really needs to be looked at very carefully. China was actually rationing electricity for a time. In the US, it didn’t really register what was happening in the rest of the world until we started to see gasoline prices go up, which were relatively small increases compared with what Europeans were seeing in gas and electricity prices. I think this issue of preemptive under-investment is something that definitely requires greater attention and focus for the stability of markets and the stability of the global economy.

Among drilling contractors, geothermal energy is emerging as a possible entry into renewables, since the skills and equipment needed for drilling conventional oil and gas wells are mostly transferable to geothermal drilling. How do you see geothermal fitting into the energy transition?

It’s early. In terms of what’s going to happen with the energy transition, you’re going to need everything. Geothermal is an area in which oilfield service companies and drilling companies could be players. It needs to be developed further, but it’s on the agenda. It wasn’t on the agenda a couple of years ago, but it is now. I participated a few months ago in a conference on geothermal at the University of Texas, and the growth in the number of attendees demonstrated the growth in interest.

Service companies are seeing themselves as technology companies. They have a lot of smart engineers and scientists, so they’re asking, how do we play in whatever is going to be the future? Is it going to be carbon capture? I don’t see how the kind of emissions reduction goals that are out there for 2050 can be achieved without carbon capture. Is it going to be geothermal? How do we mobilize our technology to play in a new game where the rules are not very clear, and where we might not even know what the game is? But we know it’s going to be a bigger game.

We’ve talked a lot about the challenges the oil and gas industry faces for 2022 and beyond. Is there anything optimistic the industry can look forward to?

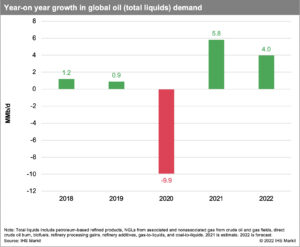

The best thing for the industry is putting the pandemic behind us and seeing economic growth. By economic growth, I mean demand will continue to grow as it is doing. In 2022, we will be back to where we were in 2019 in terms of demand, and demand will grow from there. I don’t think governments will dare go back to massive lockdowns. Instead, it will be a “new normal.”

The need for oil and for natural gas will be a requirement for a growing global economy. So, despite the rhetoric, reality bites, and reality says that economies need supplies at reasonable prices. Consumer countries will be reminded of why they want stable growing supplies, and resource-holding countries will realize that they need to be competitive to attract investment. That will certainly get us to a better place compared with the volatility and the turmoil that the industry has gone through in recent times. DC

Mr Yergin is the author of “The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations.”